India’s growth has generated jobs, as evidenced by the positive correlation between rising employment and increased consumption, challenging the narrative of “jobless growth”

The recent claim of “jobless growth” in India does not seem to hold water on the grounds of data, logic, and economic theory. It is interesting to note that there are corners that have somehow been hypothesising the phenomenon of “jobless growth” for India to such an extent that Google Trends shows a spike in searches for the phrase ‘jobless growth in India’ since 2016.

“Jobless Growth”, a term coined by Yale Economist, Nicolas Perna, in the early 1990s, refers to a phenomenon where GDP growth is either not associated with employment growth or is associated with declining employment. Numbers in India suggest a phenomenon contrary to what the “jobless growth” thesis suggests. During 2016-17 and 2022-23, data shows that employment has gone up by almost 36 percent or 17 million in absolute numbers, while GDP has shown a healthy average growth rate of over 6.5 percent during the same time.

Numbers in India suggest a phenomenon contrary to what the “jobless growth” thesis suggests. During 2016-17 and 2022-23, data shows that employment has gone up by almost 36 percent or 17 million in absolute numbers, while GDP has shown a healthy average growth rate of over 6.5 percent during the same time

Yet, the claims from certain corners that the employment data has been “doctored” also need examination. This commentary argues on the basis of fundamental macroeconomic axioms and the holy trinity of data-theory-reasoning that the claim of “jobless growth” is questionable. Rather there is more evidence in favour of India’s growth phenomenon generating jobs over the last 7–8 years.

Veracity of data: What do the numbers say?

Let us first understand the numbers. The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) maintains a rich KLEMS database, that presents annual data since 1980-81 on key macroeconomic parameters at the sectoral level. This also contains estimates on employment, based on the data from the Employment and Unemployment Survey (EUS) and the Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS). The Worker Population Ratio (WPR), based on relevant surveys, is used to estimate the total employment by multiplying it with the respective census projections of different sexes, ages, and regions. Given the paucity of data and the lack of earlier interventions to introduce multipurpose surveys, the KLEMS database is the only credible recourse for empirical growth and productivity research in India. On recent counts, the jobs creation estimates of the KLEMS database have been questioned on grounds of overestimation of population, due to the absence of the Population Census since 2011.

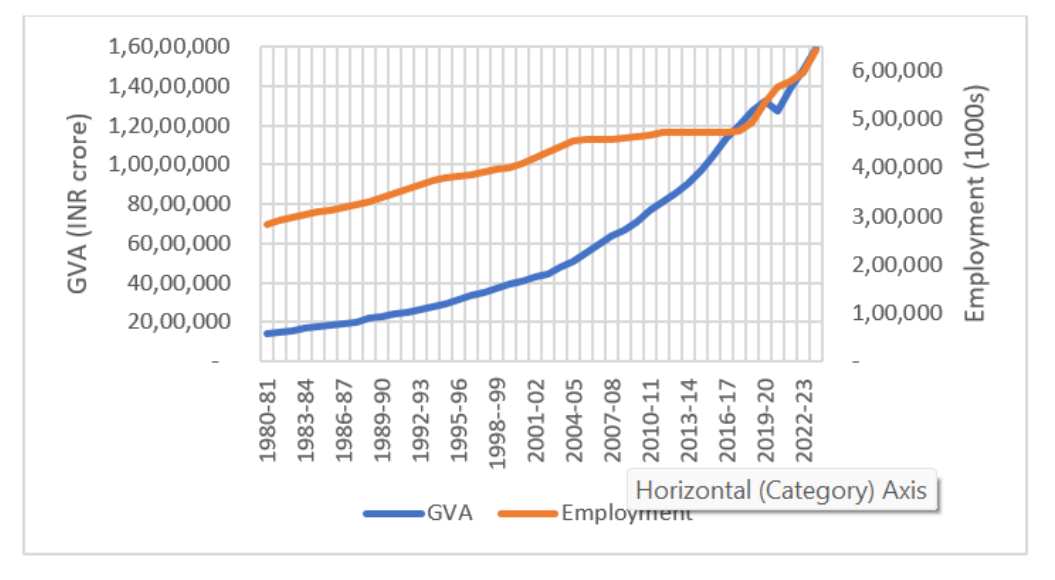

Figure 1: Gross Value Added and Employment

Source: RBI KLEMS

To put things in perspective, let’s interpret the estimates of the KLEMS database. Figure 1 shows how employment has been steadily rising since the 1980s, with a transient stagnation around 2010 to 2016. Following that, employment has bounced back with greater momentum. The stagnation period saw a structural shift, where the employment curve transformed from concave to convex, implying an increase in the rate of employment growth. Now, the PLFS data from 2017 to 2023 also suggests a similar trend. Worker Population Ratio (WPR), i.e., the ratio of employed persons to population has increased by 9 percentage points or almost 26 percent during this period (Table 1). Therefore, the consistency of the employment estimates of the KLEMS database with the PLFS does not suggest that the former is going wrong. Therefore, the rhetoric of “joblessness” really does not hold water in terms of cross-comparison of databases.

Table 1: Worker Population Ratio (in percentage)

|

WPR |

Rural |

Urban |

Rural + Urban |

||||||

|

PLFS |

Male |

Female |

Person |

Male |

Female |

Person |

Male |

Female |

Person |

|

2023-24 |

56.3 |

34.8 |

45.6 |

56.4 |

20.7 |

38.9 |

56.4 |

30.7 |

43.7 |

|

2022-23 |

54 |

30 |

42.3 |

55.6 |

18.7 |

37.7 |

54.4 |

27 |

41.1 |

|

2021-22 |

54.7 |

26.6 |

40.8 |

55 |

17.3 |

36.6 |

54.8 |

24 |

39.6 |

|

2020-21 |

54.9 |

27.1 |

41.3 |

54.9 |

17 |

36.3 |

54.9 |

24.2 |

39.8 |

|

2019-20 |

53.8 |

24 |

39.2 |

54.1 |

16.8 |

35.9 |

53.9 |

21.8 |

38.2 |

|

2018-19 |

52.1 |

19 |

35.8 |

52.7 |

14.5 |

34.1 |

52.3 |

17.6 |

35.3 |

|

2017-18 |

51.7 |

17.5 |

35 |

53 |

14.2 |

33.9 |

52.1 |

16.5 |

34.7 |

Source: PLFS

Theoretical underpinnings: “Jobless Growth” is inconsistent with “Consumption-driven Growth”

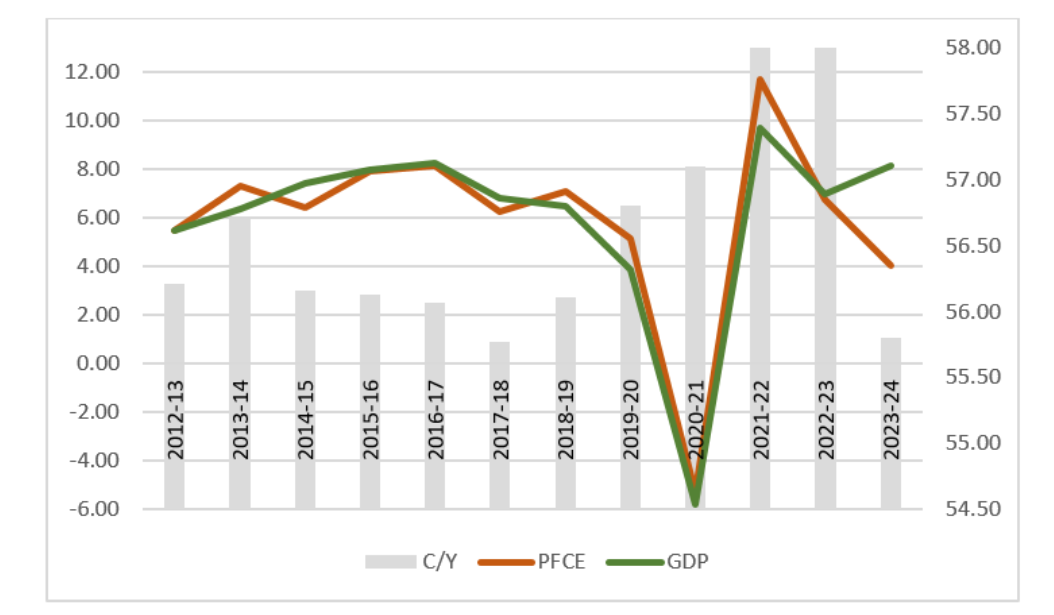

Axiomatically, for an emerging economy like India, jobless growth should be reflected in a stagnation in consumption expenditure. As claimed by some sources, if employment addition was mostly in unpaid household work, and even due to a shift to lower-paying informal jobs, it would imply a downward shift in the household income, thereby affecting consumption, especially at lower income levels. However, given the symmetry of national income accounting methods, the rise in GDP implies that there has been no such shift. Moreover, India’s growth has been predominantly consumption-driven at least till 2022-23, with a temporary snapping of the co-movement in 2023-24, and a regain of the co-movement from the Q1 of 2024-25. Contributing over 55 percent to the GDP (Figure 2), consumption has been the primary growth force, stimulating the economy through both autonomous and multiplier channels.

Figure 2: Consumption and GDP growth; PFCE-GDP Ratio

Source: MOSPI

It should be noted that employment generation is a necessary condition for consumption-driven growth in a developing economy like India, but not the other way around. Employment generation is also consistent with other forms of growth, contingent upon the allocation of capital. This can be understood better through neoclassical macroeconomics as well–treating consumption and savings as normal goods in the initial stages of income growth. However, as income grows beyond a point, there will be more savings leading to asset creation, and a decline in consumption propensity or what we call in microeconomics, the income effect prevails over substitution effects. In other words, whether axiomatically argued or proven in terms of empirical studies in various parts of the world, the marginal propensity to consume (or increase in consumption expenditure with a unit increase in income or wealth) of the lower-income groups is much higher than the higher-income groups. This implies that an increase in income of the lower income groups has a higher chance of getting into the consumption channel of the economy than an increase in income of the higher income groups (for whom the chances are higher of getting into the savings or asset creation channel). The consumption growth in the Indian economy (along with GDP growth) bears testimony to the fact that new employment generation is leading to consumption growth.

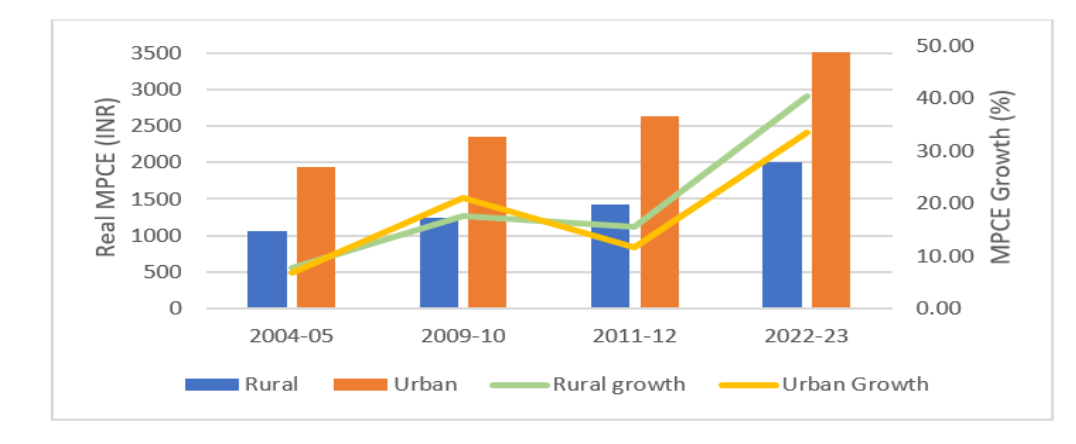

Figure 3: Real Monthly Per capita Consumption Expenditure and its growth rate

Source: HCES

This is substantiated by the Household Consumption Expenditure Survey (HCES) data, which shows both rural and urban consumption have grown at higher rates during the last decade. An economy-wide real consumption growth cannot be sustained in the absence of employment generation. Thus, jobless growth is an axiomatically impossible phenomenon for India.

Jobless or Job-full? What does employment elasticity reveal?

Employment elasticity, which provides the percentage increase in employment for a percentage increase in value-added, is a rational measure for checking the causal relation between growth and employment generation in an economy. The authors’ estimates, based on a linear econometric model, show that for the period 2017-23, there was a 1.11 percent increase in jobs for a percent increase in value added. However, during 2011-16, the employment elasticity was only 0.01. This was also the period where consumption growth marginally decelerated (both Figures 2 and 3)—further validating the economic rationale.

The consumption growth in the Indian economy (along with GDP growth) bears testimony to the fact that new employment generation is leading to consumption growth.

Further, the labour-capital ratio in the economy as a whole is around 1.11 and that for the services sector is 1.17. Thus, the supply-side argument that services fail to generate jobs due to their low labour intensity is not corroborated by these observations—rather it is the other way around. Thus, from both the supply- and demand-side, India’s economic orientation is inconsistent with any form of joblessness.

Concluding remarks

Therefore, the hypothesis of “jobless growth” does not stand in view of the cross-examination of databases in terms of their consistency, economic logic, and the empirical evidences. That does not take away the fact that the Indian economy, enjoying the demographic dividend, is yet to capitalise on its labour pool endowment. Rather, a massive opportunity exists: The large pool of labour needs to be converted to human capital through education, training, capacity building, and better health and social protection policies, to make them readily employable for Industry 4.0.